‘The Choice-I’ from "The House of Life" Celebrates Love and Relationship of D. G. Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal

A Projection of Life:

The Choice-I is a poem taken from The House of Life which consists of 101 sonnets. These sonnets of Rossetti call to mind a projection of life ‘associated with love and death, with aspiration and with ideal art and beauty.’ They have been interpreted ‘as a record of his love for his dead wife and sorrow over her death, and as a record of his passion for W. Morris’s wife Jane.’ The emphasis placed on secrecy, delayed union, and reborn rapture would seem to support the view that the sonnets are, a record of his passion for Jane. However, both Rossetti and his brother William did not like their interpretation to be done from a biographical standpoint.

The House of Life Biographical or Fictitious:

Unpleasant Reasons:

Acquaintance with these facts is necessary to understand whether the lovers referred to in The Choice-I are fictitious or they have some biographical basis. Rossetti did not approve of any Biographical interpretation obviously because of some unpleasant reasons. They are:

(i) he allowed the engagement to drag on without speeding it up to marriage;

(ii) he went away from he when he should have attended her;

(iii) he did not maintain the fidelity expected of a lover ;

(iv) despite his sympathy to her he did not take any action whereby her mental suffering could be soothed. The consignment of his poems (including the early sonnets written in memory of their love) to her grave further shows that he was conscious of his guilt.

Biographical Interpretation:

That the woman pictured in the first sonnet (i. e. The Choice-I) is modeled on Elizabeth Siddal (whom Rossetti called ‘Lizzi’) we have ample scope to establish in spite of the fact that the poet vehemently opposed such kind of biographical interpretation (the cause of which is also not unknown to us).

Who is That Girl?

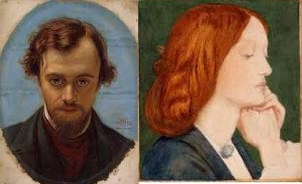

Before asserting any view it will be proper if we know something about Elizabeth Siddal, the woman whom Rossetti married later She was a ‘tall, beautiful shop-girl, with pale blue eyes and coppery golden hair’. Herself an ardent young painters she came in contact with Rossetti was on his way to become a well-known personality as an artist. Elizabeth was at that time barely seventeen.

Beloved of the First Sonnet:

|

| Dante & Siddal |

We shall, however, mention reasons why the early sonnets should be interpreted with a biographical basis. That the beloved of the first sonnet of The House of Life is based on Elizabeth Siddal is clear from certain physical similarities. As a model Elizabeth cast a peculiar fascination over Rossetti the painter with her ‘coppery golden hair’. In The Choice-I the poet has without fail referred to her ‘sultry hair’. We know from the paintings drawn on her that her hair was highly attractive, possibly sexually attractive, to him. ‘The ‘golden’ colour of her hair has been mentioned in other ways. There is the ‘golden wine’, and the glowing of her fingers ‘like gold’. Rossetti was acquainted with her artistic and shining fingers and her pointed breasts (both referred in the present sonnet and can be verified from the paintings based on her) when she sat for him as a model, and he did not fail to mention these attractive physical features of hers in his sonnet. Finally, the poet has also mentioned of her capacity to sing.

Picture of the Lover:

We have also little difficulty to recognize the poet in the picture of the lover presented in the same sonnet. Like Rossetti the lover is a believer in hedonistic philosophy. ‘Eat and drink’, therefore, h a philosophy which the poet might naturally be expected to preach to Elizabeth. Their fondness, again, for wine is clearly stated in the poem. That the earth has no requirement of their help and that the troublesome hours would be forgotten with the help of wine and song are also in accordance with Rossetti’s thought and philosophy.

A Model Lover!

Their mutual friend Deverell, who himself was captivated by her beauty, arranged through her mother for the girl to have sittings for a picture Rossetti was then painting. The sitting developed into love. A historian has described their love thus ‘Quiet, even reserved in manner, dignified in bearing, and singularly sweet in disposition she attracted young Rossetti (he was 22 or 23 at that time), who had hitherto owned no mistress but his art. In 1851 they became engaged, and the importance of this attachment upon his work (the initial sonnets were very probably written at ‘that time which were of course revised and polished later on), both as a painter and poet cannot well be over-estimated.’

Early Loved Days:

The engagement hardly proved a blessing to Miss Siddal. Unthrifty in nature and unable to manage monetary affairs carefully, Rossetti was then in no position to marry her, and the engagement drifted on unsatisfactorily. ‘Unhappily she was frail in constitution and in 1853 a consumptive tendency showed itself.’ Her suffering despite the fact of her being an artist of merit stung Rossetti himself an artist, no lightly. This is what the lover wrote about her in 1854 : ‘It seems hard to me when I look at her sometimes, working, or too ill to work, and think how many without one tithe of her genius or greatness of spirit have granted to them abundant health and opportunity to labour through the little they can do or will do.’

Notwithstanding his deep-felt sympathy for her, Rossetti proved far from what we expect from a model lover. ‘Fragile in beauty and in health, she was loved by Rossetti after his fashion, though he was unfaithful to her.’ She suffered silently but could get no redress. This led her to depend more and more on alcoholic drinks and other narcotics.

Early Married Days:

Finally, Rossetti married her in 186o, nine years after their engagement, when his financial condition improved to a certain extent. But by that time she had almost turned into an invalid. After a brief recovery of health and cheerfulness she gave birth to a child in 1861. But the child was still-born and her shock was imaginable. Rossetti too was staying more and more away from home. At this instance she began to take laudanum (i. e. opium soaked in alcohol formerly regarded as a medicine that could lessen pain. finally she died in 1862 owing to an overdose of laudanum, probably taken deliberately.

A Sorrowful Death:

Initially Rossetti was keenly affected by his young wife’s tragic death, and he decided to put his manuscript poems into his wife’s grave as a mark of penitence. This is clearly significant of his state of mind at that time. ‘The poems, he told his friends, had often been written when she was suffering and when he might have been attending to her; and he felt, what was certainly true, that his artistic preoccupation had taken him away from his home far more than was right or necessary. As a matter of fact, Rossetti was never framed for domesticity, and the union was fated to be a failure from the first. Men of his type make satisfying lovers but poor husbands. There was something peculiarly tying in this passionate act of self-abnegation, when he placed the work of his imagination between the cheek and the hair of his dead wife.’

Sorrow and Then:

To a man of Rossetti’s mood love came like a flood of joy and,. like the flood, it receded leaving some traces of sorrow behind. During the initial period he wrote sonnets commemorating the joys he received out of his love for the young beautiful woman whereas his later sonnets bore some signs of sorrow and unhappiness that sprang from her suffering and death. Both these types of sonnets were consigned to her graves.

The Remedial:

At the death of his wife sorrow entered into his soul and clouded his naturally happy disposition. But the vitality of the man was so great that its shadow soon faded to a mere speck.’ It was natural, therefore, for him to give permission to open his wife’s grave at the urgent request of his friends, and the poems were exhumed in 1869 as many of them were forgotten beyond recall. Regarding this act a critic has commented: ‘The temptation to yield to solicitations, in these circumstances, was great; but one would have respected the man more had he left alone the grave and its secrets.’

Ardhendu De

Such a well-written piece of work

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for your kind words! I'm thrilled to hear that you enjoyed the blog post about ‘The Choice-I’ from "The House of Life" and the celebration of the love and relationship between Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal. Their story is truly captivating, and it's wonderful to see it being appreciated through your thoughtful engagement.

ReplyDelete